Stephen Eckel holds Precynge, the preparation-assist device he developed to reduce IV dosing errors, an innovation advanced with support from Eshelman Innovation and KickStart Venture Services. (Photo by Sarah Daniels)

Strategic giving is critical in helping Carolina researchers translate their research into real-world solutions that benefit the people of North Carolina and beyond.

By Logan Ward

Many Carolina researchers dream of translating their breakthrough research into therapeutics and other health care products that benefit the people of the state and the world.

But researchers are trained as scientists, not entrepreneurs. And the majority of their funding comes from federal sources focused on basic research rather than translational science. That leaves those who make promising lab discoveries facing the “valley of death” — the often-fatal gulf between university proof-of-concept and commercial application or clinical use.

Fortunately, foundations and private donors provide critical funding to help researchers bridge the valley of death.

Launched in 2014 with a $100 million gift — the largest individual commitment in the University’s history — from Carolina alumnus Fred Eshelman, Eshelman Innovation is a translational engine whose mission is turning lab discoveries into health care technologies and therapeutics. Here are some ways the Eshelman gift is driving innovative research.

Barbara Vilen (right) in the School of Medicine is advancing a promising new approach to treating lupus by restoring lysosome function — work made possible through critical donor support from Eshelman Innovation. (Photo courtesy of Eshelman Innovation)

PROBLEM: LUPUS

What is it? Chronic autoimmune disease in which the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells, tissues and organs, causing inflammation and damage. Lupus often affects skin, joints, kidneys, blood cells, brain, heart and lungs.

Health impact: 1.5 million Americans have lupus, primarily women; 10-15% die prematurely

Is there a cure? No

Treatment options: The standard of care for the past 60 years or so is to dampen the immune system with corticosteroids or other compounds. The problem is that these are highly toxic and often suppress the immune system broadly, leaving patients with dangerous side effects, including vulnerability to infections.

Carolina researcher: Barbara Vilen, UNC School of Medicine Professor of Microbiology and Immunology

Breakthrough: Mysteries about the mechanistic underpinnings of lupus have made designing effective therapeutics challenging. But that’s changing thanks to a discovery made by Vilen and her team that links non-functioning lysosomes with lupus symptoms.

A cell’s lysosomes act as its waste-disposal system. Lysosomes break down old cellular components, such as proteins, nucleic acids and sugars, with the help of enzymes that become activated when the lysosomes acidify. Vilen found that lupus patients who were in inactive disease had acidic lysosomes much like healthy controls, while patients in active disease had non-acidic lysosomes.

Vilen then developed a therapeutic that could restore lysosomal acidification as a strategy to maintain inactive disease. The next steps are getting the therapeutic into human clinical trials.

“If we can treat lupus patients effectively by restoring the ability of their lysosomes to degrade cellular waste, we can maintain patients in inactive disease, alleviating side effects associated with current treatments,” Vilen says. “It’s not going to be a cure because there’s a genetic underpinning in the disease process, but it’s going to be a better treatment. I want to see patients who are not chronically tired and too incapacitated to work because of their disease. If lupus patients can have a high quality of life that can sustain them until we get more knowledge of disease mechanisms, that’s going to be a win.”

Why donor support matters: “We were basically in the valley of death and thinking, Do we give up on this? How are we going to survive? Then Eshelman Innovation provided the funding that we needed to keep the project alive. The folks at Eshelman Innovation have a team mentality and are exceptionally good at supporting innovation,” Vilen said. It might be helping fund the science or by finding partners in the pharmaceutical industry or venture capital. “They’re scientifically knowledgeable, connected to a lot of people and easy to work with.”

Ronit Freeman in the College of Arts and Sciences is developing a potential breakthrough therapy that could reverse pulmonary fibrosis — research accelerated by early-stage donor support through Eshelman Innovation. (Photo courtesy of Eshelman Innovation)

PROBLEM: PULMONARY FIBROSIS

What is it? Condition in which scar tissue builds in the lungs, making breathing difficult

Health impact: 100,000 to 250,000 Americans have pulmonary fibrosis; without a lung transplant, they usually die within a few years of diagnosis; around 40,000 of them die each year — about the same number as from breast cancer.

Is there a cure? No

Treatment options: The few existing pulmonary fibrosis treatments focus on improving quality of life and delaying disease progression.

Carolina researchers: Ronit Freeman, associate professor of applied physical sciences in the UNC College of Arts and Sciences; pulmonologist Dr. James Hagood, professor in the UNC School of Medicine

Breakthrough: Freeman is developing what could be the first treatment ever to reverse lung fibrosis. Her lab designed synthetic peptides — short chains of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins — to mimic the fibrosis-reversing properties of a protein studied by Hagood’s lab. They then tested the compounds in fibrotic lung tissue samples taken from patients.

Upon administration of the peptide mimetic, the scar tissue disappears — a reversal of the fibrosis into a healthy state. “It looks like magic,” Freeman says. “The ability to have a treatment that [would allow] patients to extend their life or completely be cured would be revolutionary.”

Freeman calls her work bio-inspired engineering. “We look at what nature does, how it self-assembles and organizes, how it manufactures, and we mimic those engineering principles to make disruptive technologies.”

Why donor support matters: “Eshelman Innovation really helped us during that early stage. We had a good idea. We had data. But then came the hard part,” Freeman said. “We needed to de-risk it, to mature the technology. Eshelman Innovation helped bring expertise from business, marketing, manufacturing, government regulation and law. They know that a convergent team is key in translating science.”

Juliane Nguyen in the Eshelman School of Pharmacy is pioneering “Zippersomes,” a noninvasive drug-delivery approach designed to help therapeutics reach the heart after a heart attack — work propelled by seed funding and guidance from Eshelman Innovation. (Photo courtesy of Eshelman Innovation)

PROBLEM: HEART ATTACK

What is it? Also known as a myocardial infarction, a heart attack occurs when the flow of blood that brings oxygen to your heart muscle suddenly becomes blocked. Your heart can’t get enough oxygen. If blood flow is not restored quickly, the heart muscle will begin to die.

Health impact: More than 800,000 Americans each year have heart attacks.

Treatment options: They typically involve catheter-based interventions, like stenting, or surgery.

Carolina researchers: UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy Professor Juliane Nguyen; UNC School of Medicine Professor Dr. Brian Jensen

Breakthrough: “One of the challenges of treating heart attacks is getting sufficient amounts of therapeutics to the heart,” Nguyen said. The heart receives only 5% of the blood volume, so most of the therapeutic agents end up reaching other organs.

“One option is injecting therapeutics directly into the heart, but that requires a cardiac surgery, often times open-chest surgery,” Nguyen said. “In our lab, we try to avoid surgery by developing strategies to deliver therapeutics that work non-invasively.”

To that end, Nguyen is developing “Zippersomes,” which combine biologic therapeutics that repair the heart with proteins that make them “sticky,” thereby leading to an accumulation of the therapeutics at the heart, where they’re needed.

“Typically, when a heart attack patient is admitted to the hospital, they receive an intravenous (IV) line, through which they receive medication and treatment. If we can show that our treatment is effective and safe, it could be integrated within the existing treatment without any need for surgery, scalpels and sutures,” Nguyen said. “It could help patients recover faster. It could prevent long-term heart failure. It could be a way of treating heart attacks without the need for surgery.”

Why donor support matters: “Eshelman Innovation was right there from the start,” Nguyen said. “They gave us seed funds to take the project off the ground. Along the way they have provided us with insights and guidance into next steps: proving the efficacy and safety of the therapeutic, understanding the unmet clinical need, researching the primary and secondary markets, and understanding the path to FDA approval.”

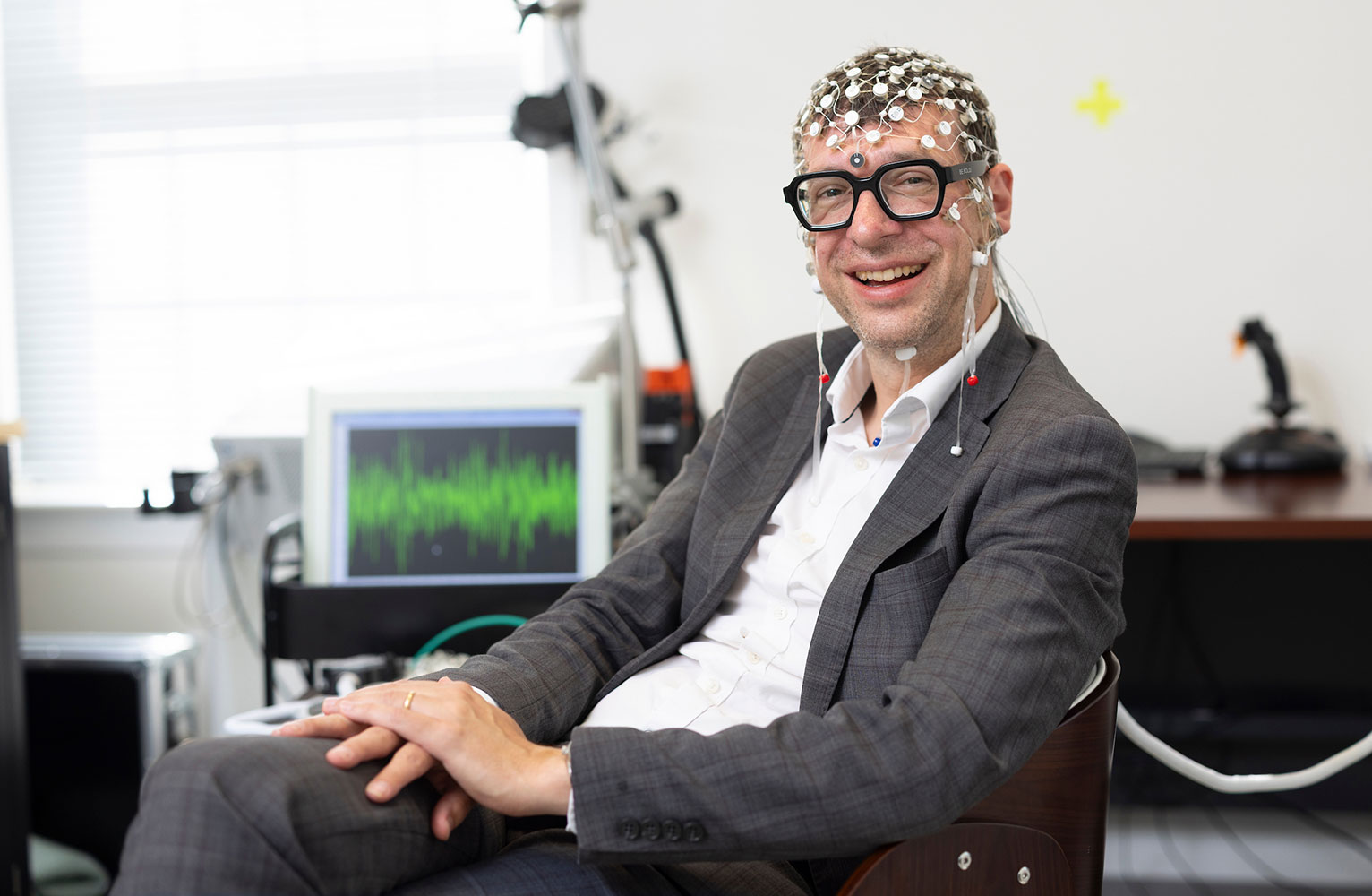

Stephen Eckel in the Eshelman School of Pharmacy is turning a critical patient-safety challenge into a practical solution. His device helps ensure accurate IV dosing — an innovation advanced with the early support and expertise of Eshelman Innovation and KickStart Venture Services. (Photo by Sarah Daniels)

PROBLEM: IV DOSAGE ERRORS

What is it? What physicians prescribe isn’t always what pharmacists dispense. One study found that 14% of the time intravenous (IV) therapy dose amounts were off by more than 10%. Neonatal and early pediatric patients are particularly vulnerable to medication errors. Studies have found that up to 17.8% of hospitalized children are subject to dosing errors; for children receiving pre-hospital care, the error rate jumped to 34.7%.

Although minimal error rates are factored into the design of the syringes, human manipulation of the device through medication preparation can exaggerate this error further.

Health impact: Therapeutic imprecision is potentially dangerous and has been shown to cause patient death.

Carolina researcher: UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy Associate Professor Stephen Eckel

Breakthrough: Eckel developed a preparation-assist device, called Precynge, that connects to an off-the-shelf syringe to ensure that the prescription and dosage match up. The device uses a volumetric process to provide consistently accurate and precise measurements for all drug preparations.

Eckel started a company, Assure Medical Technologies (now called Nuvai Medical Technologies), and began by focusing on pediatric applications. Say a pediatric patient should receive a dosage of 0.1 milliliter, a small but common volume for a dose. An error of 0.02 milliliter means a 20% dose variation. That may seem insignificant, but a baby may not be able to handle that 20% dose variation.

“Our device connects to an off-the-shelf syringe to ensure that we match up one-to-one every time,” Eckel said.

Why donor support matters: Eckel admits he did not start out to become an innovator. He fell into it once he recognized the problem of IV dosage errors. “I don’t always know what I should be asking,” the self-proclaimed accidental entrepreneur said. “I don’t know what the next steps are on the journey. I might not have the right contacts. Eshelman Innovation provides advice, assistance, resources. They’ve been a tremendous benefit to me.”

Eckel and his startup also received critical support from KickStart Venture Services (KVS), a core program of Innovate Carolina, the University-wide initiative for innovation and entrepreneurship at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Related Stories