Professor Flavio Frohlich received a Distinguished Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation for his neurostimulation approach to treating pregnant women experiencing depression.

Revolutionizing how to interact with the brain to treat depression in pregnant women — without pharmaceuticals

Written by Kay Langley ’22, ’24 (M.A.)

Photos by Jeyhoun Allebaugh

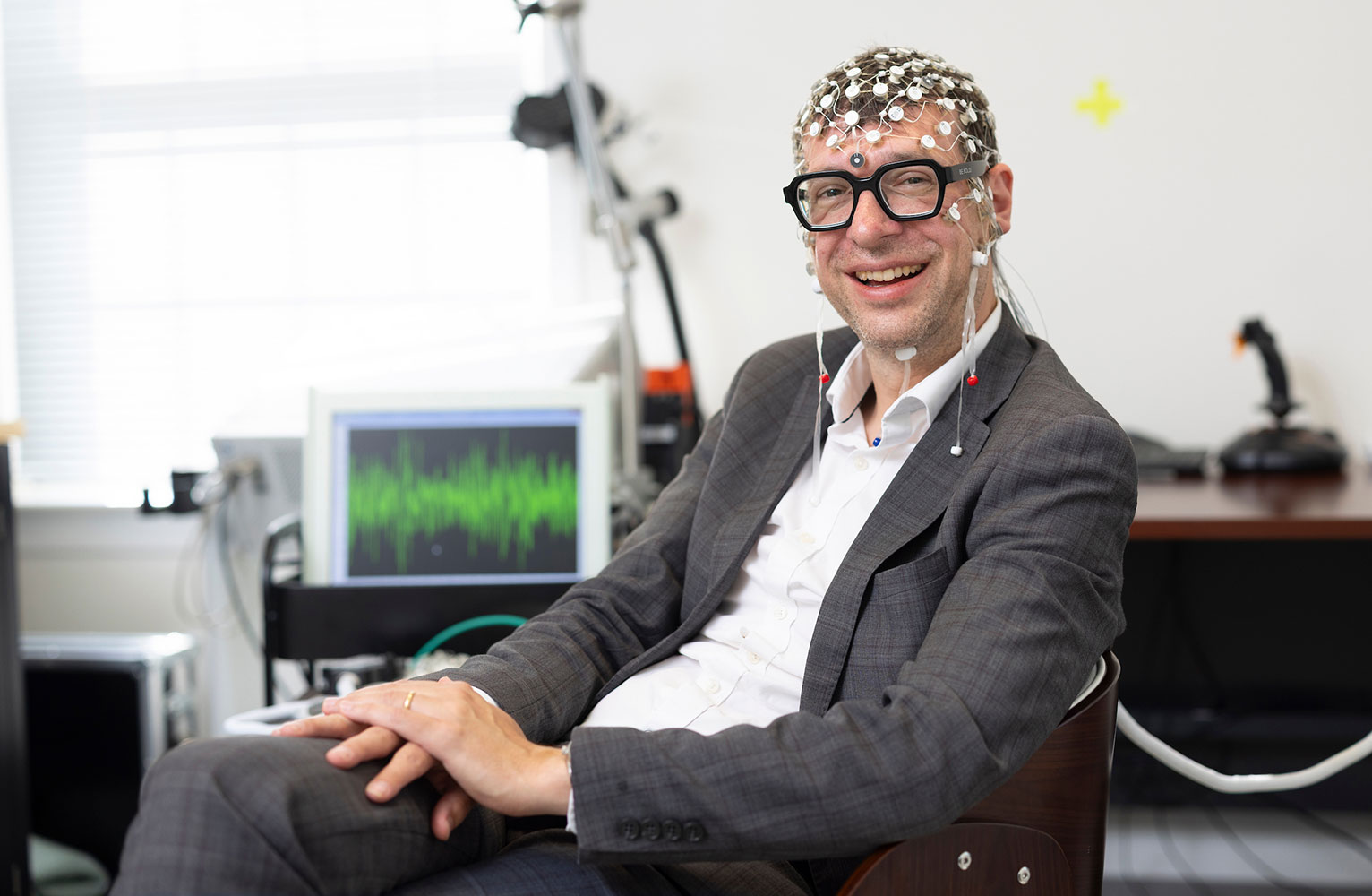

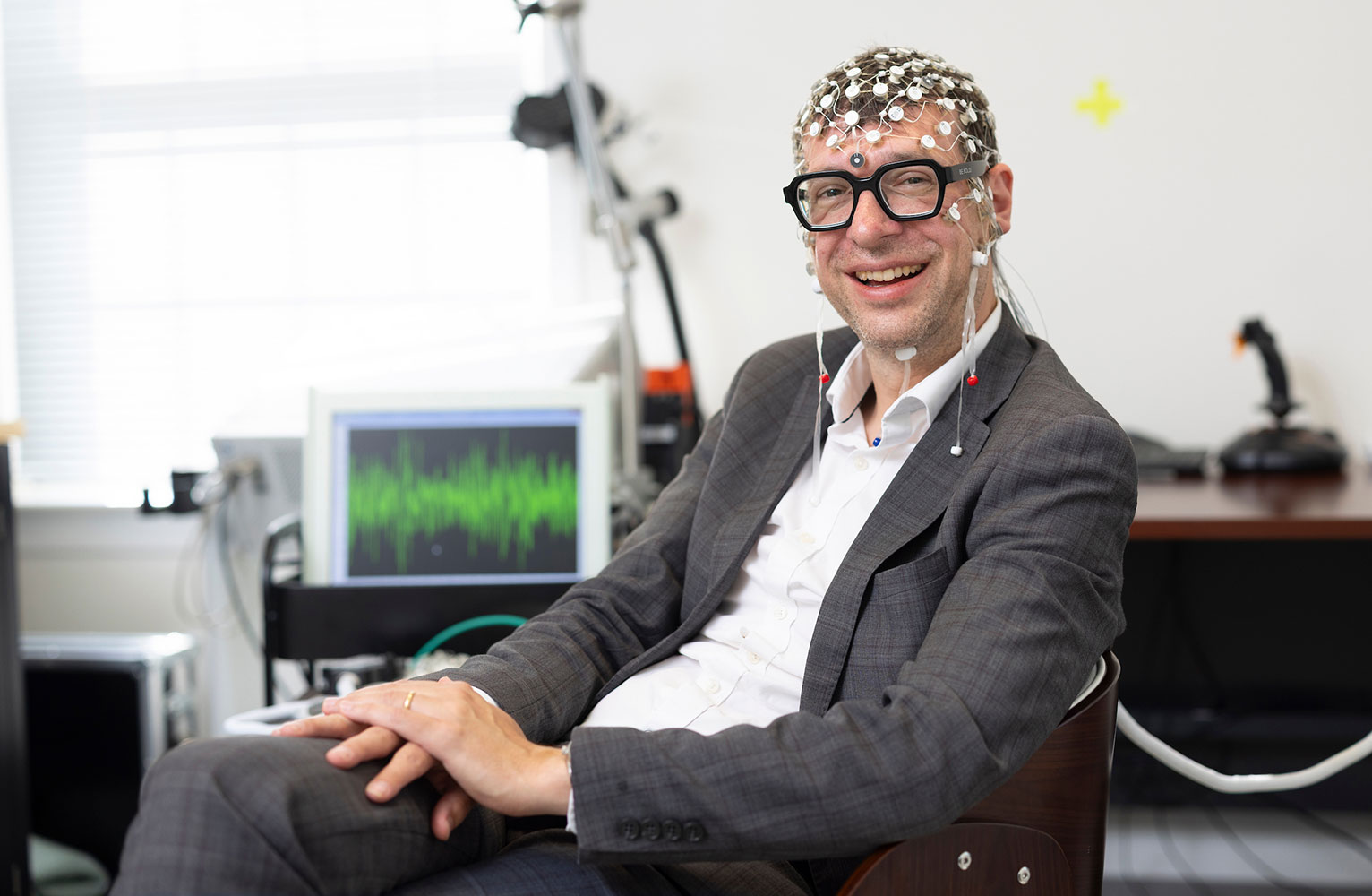

Flavio Frohlich, director of the Carolina Center for Neurostimulation, is leading a team that’s reimagining how we treat depression — not with medication or talk therapy, but with electricity. His team uses transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), a non-invasive method that uses weak electrical currents to gently reshape brain activity.

“We study noninvasive brain stimulation with the goal of developing new treatments for psychiatric disorders like depression and anxiety,” Frohlich said. “It’s not pharmacological. We’re engaging in a dialogue with the brain’s own rhythms.”

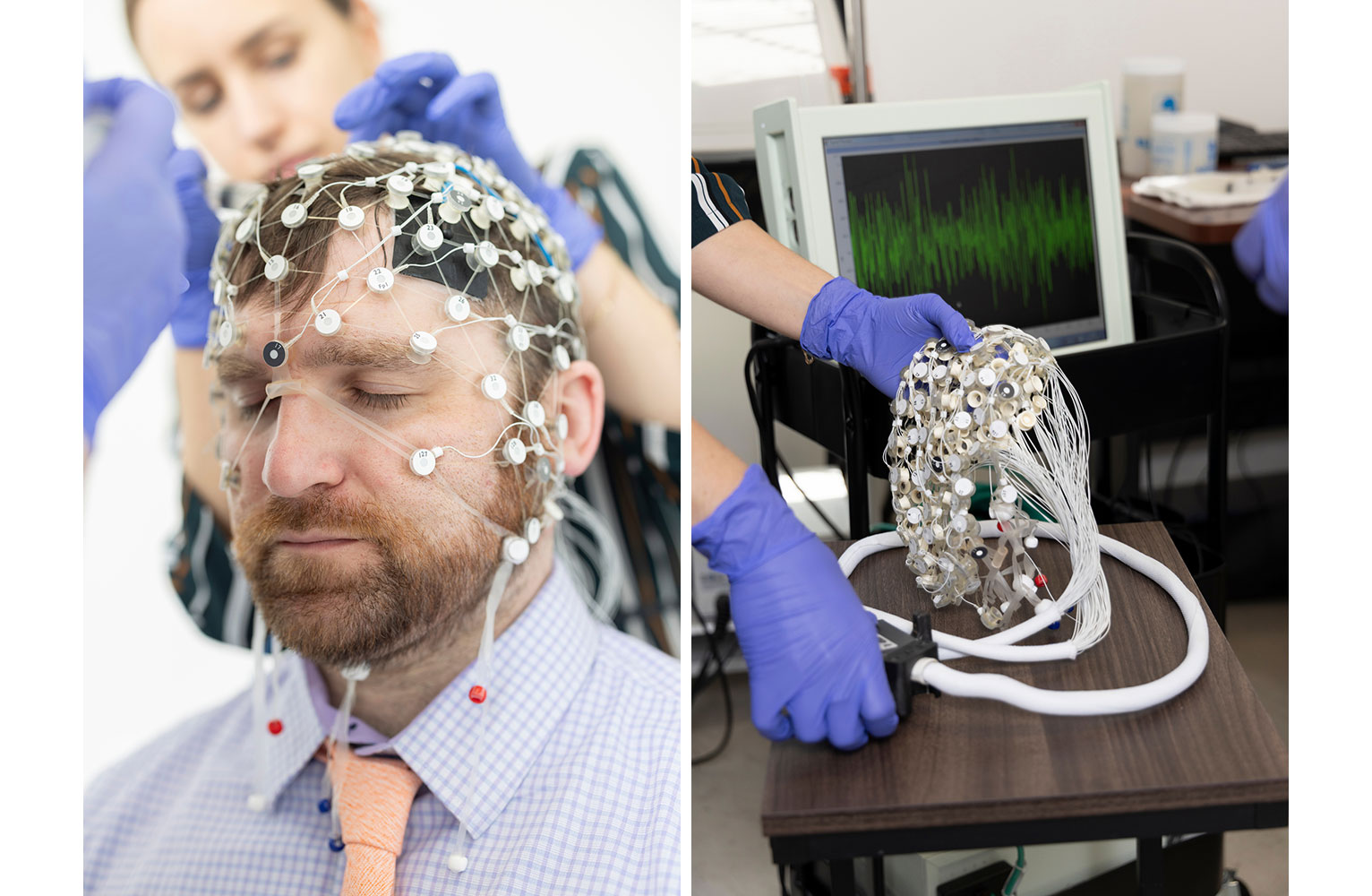

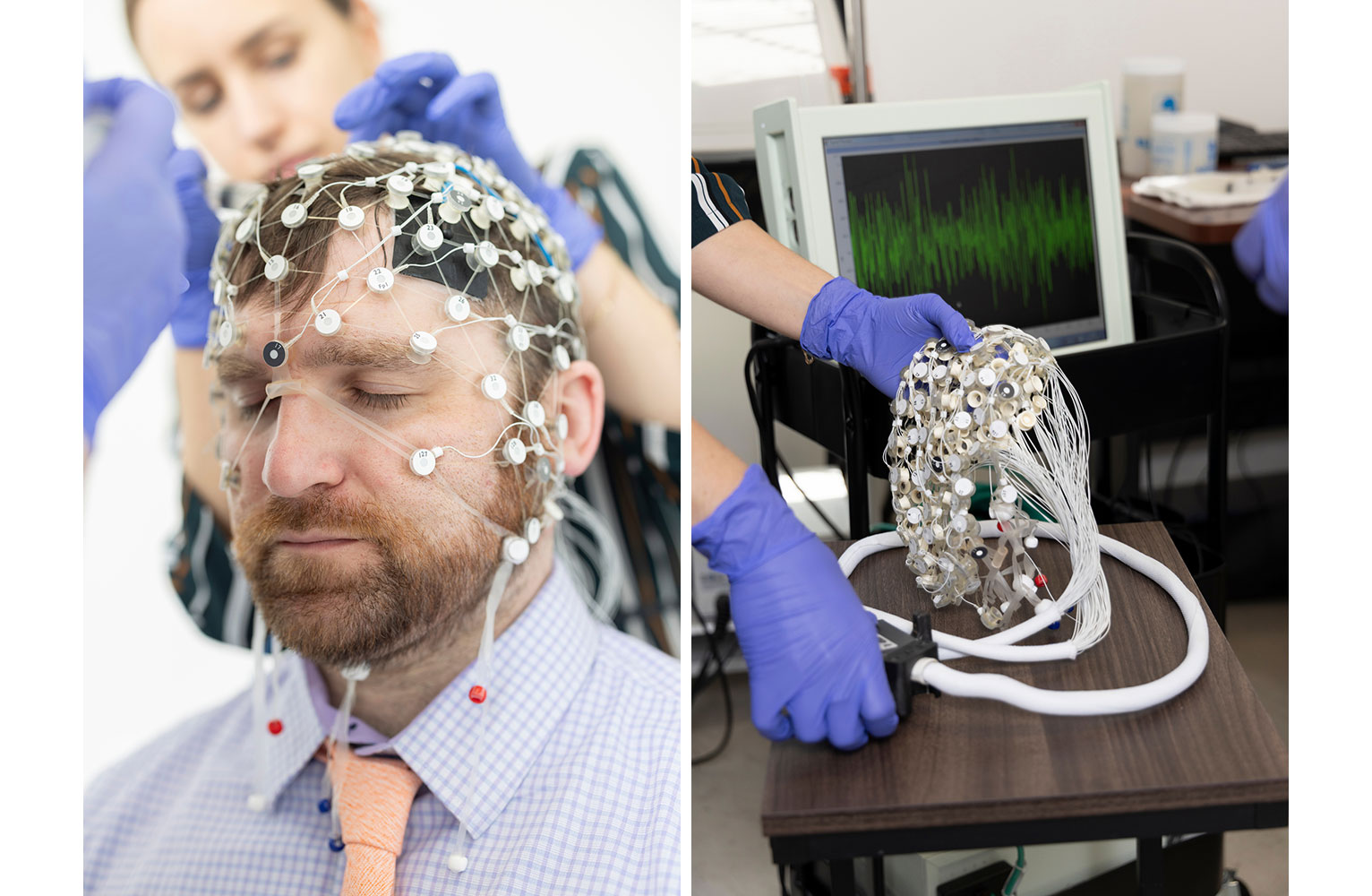

That “dialogue with the brain” isn’t metaphorical. Frohlich’s research taps into the natural electrical patterns the brain uses to organize itself. With tACS, electrodes are applied to the scalp, delivering rhythmic, low-energy electric currents designed to subtly influence these patterns. “The brain is electric. It generates its own rhythms. So we thought — what if we could speak that language to help it heal?” Frohlich explained.

Fifteen years ago during a postdoctoral fellowship at Yale, Frohlich discovered that electric brain signals weren’t just measurable, they were essentially how neurons communicate within our brains. That realization became a turning point. “I started thinking about how to take this biological principle and apply it with technology to actually help patients.”

Now director of the Carolina Center for Neurostimulation at UNC School of Medicine and professor in the departments of psychiatry and cell biology and physiology, Frohlich has built a multidisciplinary research program studying that groundbreaking discovery and how to use it to treat mental illness.

“What we’ve actually done is we’ve looked at how brain rhythms change when people recover from depression, and we found some new features of how the activity patterns change. We built an approach where we’re measuring these features in individual patients and using that to inform our stimulation.”

Story continues below When Music Meets the Mind

Flavio Frohlich teamed up with Johnny Gandelsman, Carolina Performing Arts’ first-ever curator-in-residence, to demonstrate how the brain synchronizes with sound during a live brain-mapping session.

WATCH WHEN MUSIC MEETS THE MIND

Serving a unique population

His most recent study, funded by a 2025 NARSAD Distinguished Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, targets a particularly underserved population: pregnant women experiencing depression. Frohlich notes that while medication that treats mental health is safe during pregnancy, some women are reluctant to use it, either due to personal concerns or societal stigma. That creates a gap in care that non-pharmacological treatments like tACS might help fill.

“Depression during and after pregnancy doesn’t just affect the mother, it impacts the child, the family, everyone,” said Frohlich. “It is quite prevalent and there’s a huge unmet need.”

The grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation is crucial to making this kind of cutting-edge science possible. “This type of research is extremely innovative and sometimes too novel for traditional federal funding streams like the NIH,” Frohlich explained. “Philanthropic foundations give us the runway to ask big questions, explore bold ideas and open new clinical indications, like this one in pregnant women.”

The study invites participants to the research center for five consecutive days. Each session begins by measuring brain activity to create an “electric fingerprint” unique to the individual. That fingerprint informs the stimulation protocol, essentially customizing the electrical signal to the patient’s specific brain rhythms. The actual stimulation lasts about 40 minutes, during which participants simply rest.

“It’s incredibly safe,” Frohlich said. “Most people feel nothing, maybe a slight tingling or pressure from the electrodes. But there’s no surgery, no sedation, nothing invasive.”

This trial builds on earlier studies using similar neurostimulation in non-pregnant populations, where Frohlich’s team reported remission rates as high as 80% in pilot studies. “We’re seeing that the more personalized the treatment becomes, the better the outcomes,” he said. “This new generation of individualized stimulation is really exciting.”

If the study’s early promise holds, the next step would be a larger, placebo-controlled trial. But Frohlich is already thinking beyond the lab.

Scaling science

One of the reasons he’s so passionate about tACS is its potential scalability. Unlike many forms of psychiatric treatment that require hospital visits or expensive equipment, tACS runs on battery-powered devices that could one day be used at home.

“Our vision is that this treatment could be shipped in a padded envelope and sent to anyone in North Carolina or across the United States to offer technology-based treatment at home,” Frohlich said. “For pregnant women who may have trouble getting to a clinic regularly, that could be a game-changer.”

Frohlich’s team demonstrates the use of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), a non-invasive method that uses weak electrical currents to gently reshape brain activity.

Frohlich remains focused on the people his work is meant to help. He’s especially passionate about destigmatizing depression and making sure people know that it’s a medical condition that can be effectively treated.

“Depression is a biological illness, like diabetes,” he said. “People deserve help, and they should know that help is out there. Participating in clinical trials is one way to access promising new treatments that aren’t widely available yet.”

Multidisciplinary collaboration at work

Frohlich is quick to credit the vibrant, collaborative environment at Carolina for enabling this work.

“Maternal mental health is a big priority at Carolina, on the clinical and research side. We also have an amazing infrastructure for clinical and research programs. So Carolina is a wonderful place for this research because our collaborators have such deep expertise in psychiatry and maternal health,” he said. “The environment and setting ultimately determine the success of such research programs, and I am deeply grateful for what we have here at Carolina.”

His lab is collaborating with researchers across the UNC School of Medicine for this study, bringing in a diverse field of experts to tackle the unique challenge of serving the pregnant population.

From the department of psychiatry, Samantha Meltzer-Brody, Assad Meymandi Distinguished Professor and executive dean of the UNC School of Medicine, and Julia Riddle, assistant professor, are contributing expertise in women’s mood disorders and postpartum depression. Michael Evers, assistant professor in the department of general obstetrics, gynecology and midwifery, brings expertise on obstetrics primary care.

From the Frohlich lab, psychiatrist Zachary Feldman and postdoctoral fellow Athena Stein are taking point on applying their tACS methodology to this unique patient population. Mengsen Zhang, assistant professor at Michigan State University and former postdoctoral fellow with Frohlich provides her computational expertise for designing the stimulation waveforms.

But at the heart of it all, Frohich said, are the trainees.

“All the cool research I’m talking about is really the work of trainees. Carolina has such a fantastic caliber of trainees from across the globe who are working incredibly hard and doing amazing work to move the science forward.”

That spirit, combined with cutting-edge science and a commitment to real-world impact, may one day bring the lab’s neurostimulation treatments into homes across the country. For now, Frohlich and his team remain focused on listening to the brain — and helping it find its rhythm again.

Related Stories