Rhiannon Giddens (Photo by Ebru Yildiz)

The Southern Futures Artist-in-Residence at Carolina Performing Arts brought partnership, connection, history, advocacy and joy to UNC-Chapel Hill.

By Angela Harwood

Rhiannon Giddens first earned widespread acclaim as the lead singer, fiddle and banjo player of the Carolina Chocolate Drops. The MacArthur “Genius” grant recipient, children’s book author and composer of opera, ballet and film has five solo albums, two GRAMMYs, and a Pulitzer Prize under her belt. Many may recognize her as Hallie Jordan from her recurring role on the last two seasons of “Nashville.” You’ve most certainly heard her playing banjo on Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold ’Em.” Currently, she’s the artistic director of Silkroad Ensemble, founded by Yo-Yo Ma. It’s no wonder that NPR named her one of its 25 most influential women musicians of the 21st century.

After a multi-year artist residency at Carolina Performing Arts, Giddens is a true Tar Heel who forever has a place in our hearts.

An open-ended experience

Giddens said “it was an easy yes” when Carolina Performing Arts (CPA) asked her to be the inaugural Southern Futures Artist-in-Residence.

“What Carolina Performing Arts does is wonderful, and the people are fantastic,” she said, noting her existing relationships and previous performances in Chapel Hill. She was also drawn to the Southern Futures residency program’s structure, which provided her time, resources and support, with no expectations of the outcome.

Bridging UNC-Chapel Hill’s College of Arts and Sciences, University Libraries and CPA, Southern Futures is a collaborative network for students, scholars, creators and community leaders doing extraordinary work to reimagine the American South. The Southern Futures Artist-in-Residence was tailored to serve the needs of the artist so the artist could, in Giddens’ words, deliver the things that only she can uniquely deliver. That meant helping Giddens dig into archives and dive into the history of America.

“To have an open-ended research residency, to have access to the archives and be able to do primary source research with the kind of support you usually only get when you’re a doctoral student, was great,” Giddens said. “It was a unique residency designed for me — as a sort of embodied practitioner and performing researcher.”

“Carolina Performing Arts prioritizes partnerships and relationships,” added Alison Friedman, the James and Susan Moeser Executive and Artistic Director of CPA. “The residency had to be bespoke, not prescriptive. It takes a special artist to be open to this kind of trusting partnership. Rhiannon was the perfect match.”

Matchmaking artistry

Giddens’ residency began in spring 2022 with the goal of “highlighting stories untold and voices unheard,” she said. “My aim was to celebrate the cultural contributions of those who came before us in my art and to bring to light the impact of Black and Indigenous populations that resided in Chapel Hill.”

Access to past research, archival recordings, existing communities and faculty thought-leaders with shared interests was integral.

“Carolina Performing Arts is a matchmaker between resources, people and opportunities at UNC, and our global network of artists,” said Friedman. “We know the areas of inquiry on our campus and what brilliant artists and minds are out there who could contribute to what’s going on here.”

Artist in the archives

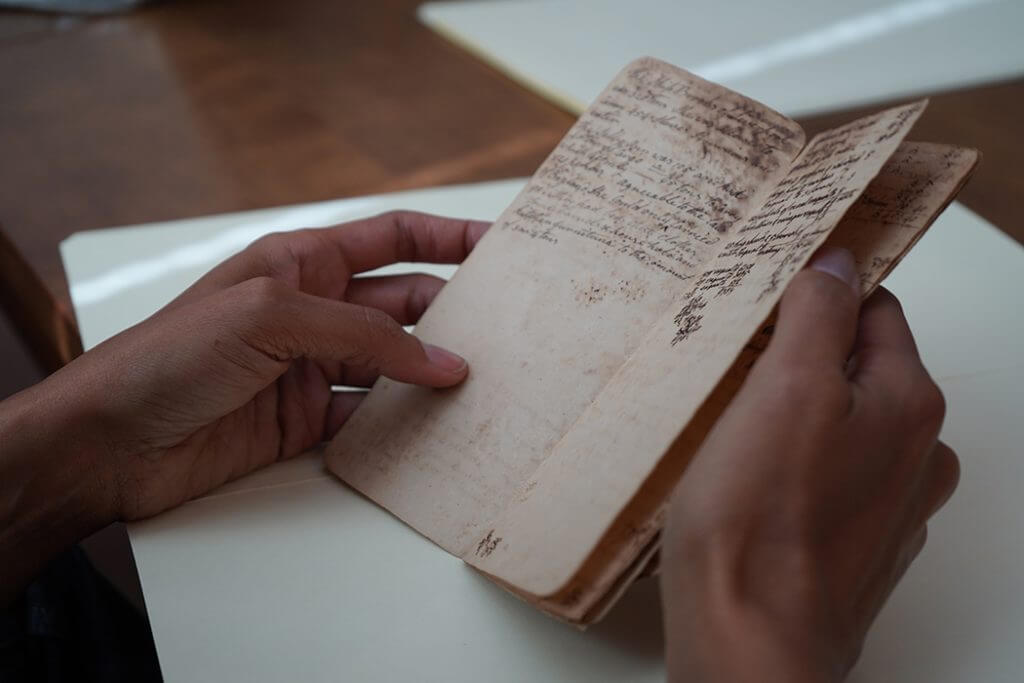

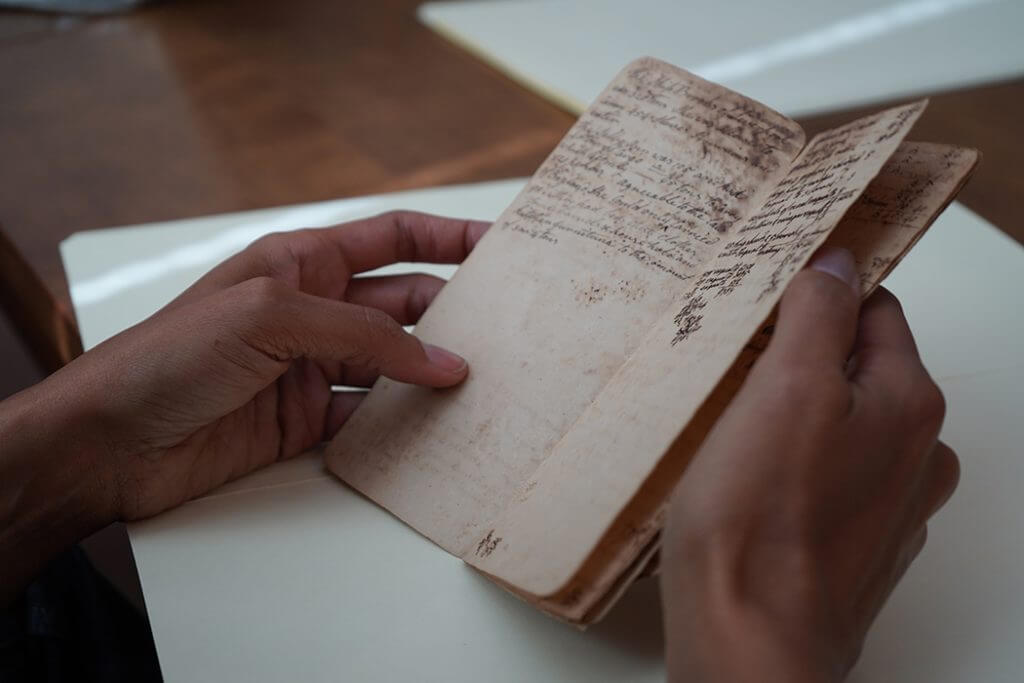

Giddens’ work centers on history, uncovering and lifting up overlooked people and forgotten or erased musical origins. Until her residency, she conducted much of her historical research digitally, finding sheet music from the 1800s, advertisements for enslaved people, ads for runaways. “These kinds of things have played a huge part in my songwriting and composition,” she said, “but I’ve never had the opportunity to hold documents in my hand, to chase things down, to really dig into things.”

Giddens spent hours delving into the robust archives of Wilson Library with the help of Wilson Library archivists, Southern Futures Archivist and Digital Project Lead Taylor Barrett, and Southern Futures Research Assistant Callie Beattie. Prior to and between Giddens’ campus visits, Beattie combed through the library’s collections to find archival materials and moments of cultural exchange from the 1800s to the early 1900s. Beattie shadowed Giddens as much as possible to gain further insight into what materials would be of potential interest to the artist.

Rhiannon Giddens and Callie Beattie explore the archives at Wilson Library. (Photo by Taylor Barrett)

“Rhiannon and I discussed her work, interests and the avenues she wanted me to explore,” Beattie said. “But having the opportunity to listen to her talk with others who are just as passionate was a significant source of inspiration for my work as her research assistant.”

“I needed to see things for myself,” Giddens said about her time in the archives. “I was able to get a feel for a time period, for rural life in a certain aspect in certain parts of the state.”

Giddens recalled two surprising moments in the archives. One, not so nice: “I opened a folder and realized it was full of sales slips for a person, and that messed me up. It ended the research session early. These things happen. It was an important thing for me to have to deal with.”

The other surprise: historian Malinda Maynor Lowery’s ’02 (MA), ’05 (PhD) tapes for a documentary about the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina. “The very last thing that was pulled for me was footage that showed a drum at the Lumbee powwow, a drum I used to sing with. It was beautiful in a way and a neat wrap up for me.”

Giddens said that what she learned in the archives has infused her work in different ways. “It’s not always as clear as an advertisement for a person for sale turning into a song.”

Story continues below…

10 Highlights from Rhiannon Giddens’ Southern Futures Artist Residency at Carolina Performing Arts

SEE TOP-10 LIST

From the archives to the stage

As Giddens continued her research, she made important connections with communities across campus, including the UNC American Indian Center. In spring 2023, she visited a meeting of the LandBack Abolition Project and heard from students and faculty conducting archival research into the campus’s land-based origins: how the University was built on and later profited from the sale of near and distant Native lands and from the labor of enslaved people.

She was struck by historic campus maps and knew she wanted to bring the maps and other archival and modern images of Native communities and traditions to the stage during her culminating performance, featuring Martha Redbone, Pura Fé and Charly Lowry.

“As someone who is, I like to say, ‘native adjacent,’ in my connections and family, this is something I’m interested in being a facilitator and advocate for,” said Giddens, who grew up in the North Carolina Piedmont.

Rhiannon Giddens (center) and collaborators at the Ackland’s “Past Forward” exhibit. This group generated the conversation about identity and place that inspired a new song, literally written overnight! (Photo by Amanda Graham)

The performance was part of a two-day collaboration, “Roots & Reclamation: Native North Carolina & the LandBack Movement,” featuring several open classroom events and an American Indian powwow. The evening before the performance, Giddens, collaborators and community members gathered at the Ackland Art Museum for a conversation about land and music, coinciding with the exhibition “Past Forward: Native American Art from Gilcrease Museum.” The conversation inspired a new song, “When Are We Us,” literally written overnight and performed as the last song of Giddens’ final concert during her residency. Watch a clip from the performance here.

“I’m here as a facilitator and to use my platform to tell this compelling story that I understand because of my heritage,” Giddens stressed. “So I felt the concert had a very fruitful ending and was a wonderful culminating event.”

“Rhiannon has used her residency and platform to uplift and elevate Native voices and issues and to advocate for us on campus and beyond,” said Danielle Hiraldo, director of the American Indian Center. “I very much appreciate her approach to developing partnerships and facilitating meaningful conversations.”

Fostering dialogue

“Omar,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning opera composed by Giddens and Michael Abels, is a great example of art fostering dialogue. The opera details the life of Omar ibn Said, a West African scholar enslaved in the Carolinas, drawing details from ibn Said’s 1831 autobiography. Co-commissioned and co-produced by CPA and Spoleto Festival USA, the 2023 performance of “Omar” in Chapel Hill was a powerful moment.

“Now, everyone who was in the audience knows Omar’s story — a story they wouldn’t have known otherwise,” said Friedman.

While “Omar” was in the works before Giddens’ residency began, her routine presence on campus led to several opportunities for the community to learn more about ibn Said’s life and engage in constructive dialogue centered on topics ranging from the historical conditions of slavery and its impact on the economic realities of the contemporary South to the opera’s place and significance within the operatic canon.

“The collaboration with ‘Omar’ was amazing, and my favorite time seeing it was at Chapel Hill,” Giddens said. “That was not just something that came out of the residency, but because the residency was flexible, we were able to fold it in. The timing of everything was beautiful and fortunate, but also utilized. The way the residency connected everything was really well done.”

The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC-Chapel Hill stewards a collection of archival documents written by or depicting ibn Said. The University Libraries hosted multiple pop-up exhibits for donors and Friends of the Library, students and the broader community, to view — and even handle — these materials.

A small account book with expenses belonging to Phineas Nixon while on the voyage of the Sally Ann from Beaufort, N.C. (photo by Taylor Barrett)

Chaitra Powell, Kenan Curator of the Southern Historical Collection, remembered a conversation among Giddens and visitors from the Ar-Razzaq mosque in Durham. “Rhiannon was there, totally low-key in a hoodie and sneakers, just listening and being a part of the conversation,” Powell recalled.

The visitors from the mosque commented on how the story of Muslims in America have been erased, and how Omar would have been one in thousands of enslaved people of Muslim faith. Giddens confirmed she understood and shared how she tried to invoke a spirit of community within the opera, showing where Omar came from and how he might have connected with others of similar faith throughout his journey to and time in the Americas.

“The dialogue also included mentions of the role of the archive and how the papers that are kept and preserved can only take us to a certain level of understanding,” Powell continued. “We have to draw on other ways of knowing — music, perhaps? — to have a more complete picture of the past.”

‘Rehumanize fragmented bones’

Glenn Hinson, associate professor of anthropology and American studies, also spoke about the need to “draw on other ways of knowing” when it comes to historical research and the roles of artists. “When academics think of research, we tend to think dryly,” Hinson noted. “Artists invite us to remember the fullness of humans. Rhiannon does this in obvious ways because she addresses history in her music and performances.”

Hinson was one of many campus thought partners Giddens met with during her visits. “I enjoyed working with and going to Hinson’s classes,” Giddens shared. “He’s working very deeply in subjects that I’m interested in and connected to.”

Visiting Hinson’s class, “By Persons Unknown” (Photo by Taylor Barrett)

Hinson’s teaching and research focus on the Descendants Project, a collaboration among Hinson, his students, local chapters of the NAACP and the Equal Justice Initiative. The project aims to uncover the complete stories of victims of lynchings, their legacies and their descendants in order to advocate for public memorialization of those victims. Hinson said the project intrigued Giddens for a number of reasons.

“One being that it attempts to tell the story from the bleached fragments of bones that the archival record offers us,” Hinson said. “We’ve got these tiny fragments, but they’ve all been cleaned of humanity. One of the things that Rhiannon does so well is try to find the historical fragments and craft stories around them — stories that compel people to listen and that offer a glimpse into the people who once enlivened those bones. That glimpse invites hearers to rethink what they know.”

Giddens and Hinson’s students talked about their respective research processes. “For her to hear students talk about how they’re trying to rehumanize fragmented bones and restore lives and families and stories, and how they’re doing it differently from how she’s doing it, but in a completely parallel way — and then for them to hear how she reanimates through song,” Hinson concluded, “That was a once-in-a-lifetime exchange.”

Shared moments of joy

The impact of Giddens’ residency on the campus community is rich and varied. As Friedman noted, “The arts show us our shared humanity and create moments of shared joy.”

Giddens brought so many of those moments to Carolina: from her stellar performances and passionate conversations with community members to surprise moments like the “Joe Jam” in the last month of her residency.

Giddens and former Carolina Chocolate Drops bandmate Justin Robinson led a spontaneous jam session outside the steps of Wilson Library in honor of the revered string band elder Joe Thompson. They invited others to join, resulting in one of the most intimate and joyous moments of her residency.

Giddens and Justin Robinson host a jam session outside of Wilson Library. (Photo by Jeyhoun Allebaugh)

“Rhiannon felt part of our community and we felt part of hers,” Friedman said. “Sometimes you need constructive escape. Moments of shared joy can be profoundly healing and don’t have anything to do with tough conversation or changing minds.”

Giddens also stressed the importance for artists, or anyone, to chase joy. “Chase your joy and find your purpose. You can’t live in joy all the time, but you need to find those points of joy.”

What’s next

For those who missed Giddens’ performances at Carolina during her residency — don’t worry! You’ll have another chance. Giddens will be back in Carolina Performing Arts’ 2024-25 season, on November 20, as artistic director of Silkroad Ensemble.

“It’s a gift to come back so soon and hopefully see the friends I made over the residency,” said Giddens. “Silkroad is so in congress with the things that I did with CPA and in the residency — so it’s all a piece really.”

Giddens’ experience as an artist-in-residence at Carolina will have a deeper impact than what we can see right now. “Maybe I’ll build on something I did during the residency,” she said. “This is now an ongoing relationship that will continue to transform.”

She’s currently writing a popular history book and may be doing something else in the realm of opera. When asked if there may be more opera in her future, she said, “Watch this space.”

We couldn’t do it without you.

Rhiannon Giddens’ Southern Futures Artist-in-Residency was supported by the William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust and matching gifts from CPA’s devoted community. Ticket sales for Carolina Performing Arts cover approximately 10% of what it costs to present their season and support artists residencies. Without private support, Friedman noted, “It simply would not happen. We’re deeply grateful for those who supported ‘Omar,’ Southern Futures and Rhiannon’s residency. It’s a testament to the people who believe in this vision of using the arts to uplift society.”

Make a gift online to support the performing arts.

CPA and Southern Futures fully documented Rhiannon Giddens’ Research Residency and Omar at Carolina. Explore the links to learn more about everything Giddens did at Carolina.

Campaign for Carolina Impact

Southern Futures, a collaborative network for students, scholars, creators and community leaders doing extraordinary work to reimagine the American South, and the Southern Futures Artist-in-Residence at Carolina Performing Arts, were founded during the Campaign for Carolina. And the James and Susan Moeser Executive Artistic Director of Carolina Performing Arts, currently held by Alison Friedman, was endowed during the campaign, which raised more than $5 billion for students, faculty, research and patient care at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Related Stories